Galapagos National Park

The Galapagos archipelago, made up of 13 major islands, six minor ones and 42 named islets plus scores of unnamed smaller rocks and islets, is Ecuador’s preeminent national park and indeed one of the preeminent in the world, not only because of Darwin’s famous observations but for the creatures that inspired them.

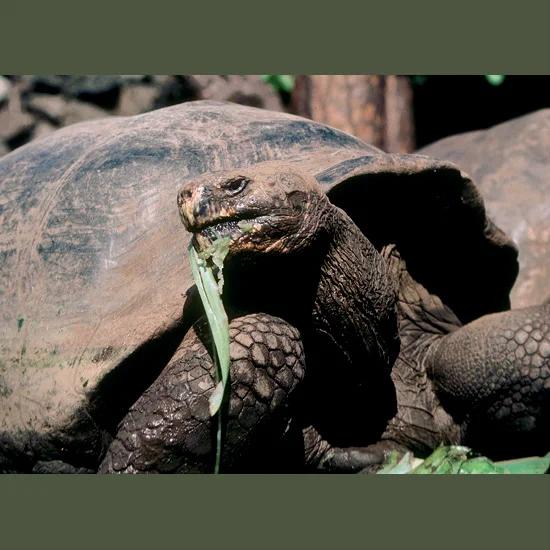

Here are giant tortoises weighing up to 550 pounds (250 kg), living 150 years or more, such as once roamed most of the world’s continents, including Europe and the North American midlands. Now giant tortoises exist only on the small Indian Ocean atoll of Aldabra in the Seychelles and here, where their inter-island differences, noted by Darwin, show adaptations that enabled them to survive in varied environments— higher shells and longer necks and limbs on islands where they had to stretch for food, modifications discarded where food was easily reachable on the ground.

Here are the famous finches which, as Darwin observed, have at least 13 different bill adaptations to deal with different foods, from soft insects to hard seeds, and some have evolved tool-using techniques enabling them to pry edibles from hidden crannies with sticks.

Here are flightless cormorants with wings shriveled through eons of disuse so they are functionless in the air, though the birds still stand “hanging them out to dry” after fishing forays just as normally-equipped cormorants do.

Some Galapagos iguanas live terrestrial lives, great golden dragons clumping about, looking dangerous but subsisting on flowers.

A marine variety has returned to the sea, dark, prehistoric-looking, up to a yard (1 m) long with spines from head to tail, carrying young on their backs and grazing on watery vegetation as much as 35 feet (11 m) below the ocean surface, world’s only seagoing lizards.

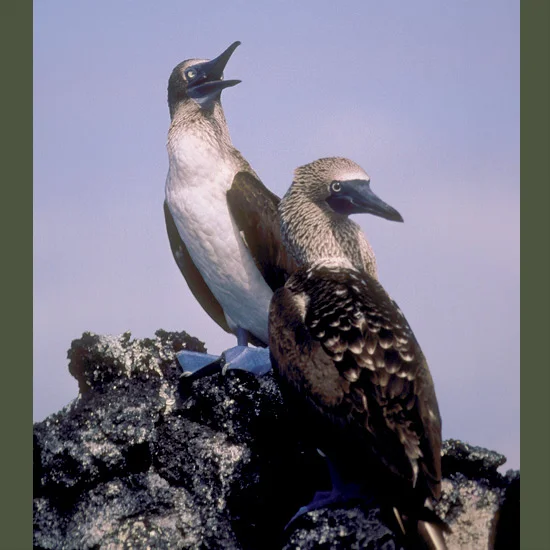

Here are the world’s farthest-north penguins, along with three kinds of boobies—blue-faced, red- and blue-footed—along with waved albatross, swallow-tailed gulls (which feed nocturnally by sonar using red eye-rings), red-billed tropic birds, flamingos, magnificent frigate birds with scarlet throat pouches inflated for courtship, and endemic Galapagos hawks and doves. Two-thirds of resident birds are endemic—found nowhere else—including four mockingbird species.

In and around the sea are sea lions, fur seals, and engaging little scarlet Sally Lightfoot crabs.

Because they have not been harassed by humans—except indirectly by introduced now-feral goats and pigs—all the wildlife are enchantingly fearless of visitors.

Each of these islands, once known as the Encantadas or Enchanted Isles, is different.

Santa Cruz has the highest human population, also facilities where visitors can arrange overland or boat tours, stay at hotels, and see the Charles Darwin Research Station which has park information and readily visible giant tortoises. Except for the Tortoise Reserve, a day trip, most are in or within walking distance of Puerto Ayora. Most visitors arrive by air at Baltra Airport and transfer from there to Santa Cruz or to prearranged tours.

Among most-visited islands:

Santa Fe, one of the best places to see land iguanas and giant cacti over 10 yards (10 m) tall.

Bartolomé has Galapagos penguins; sea turtles nest on beaches January–March.

Seymour, outstanding seabird nesting grounds, especially blue-footed boobies in elaborate courtship.

San Salvador (aka Santiago or James), marine iguanas sun themselves on black volcanic rocks and fur seals swim in crystalline pools, often with snorkelers.

Rabida (aka Jervis), hundreds of sea lions and their babies play on dark red sand, and bright flamingos feed on a marshy lake.

Genovesa (aka Tower), main red-footed booby colony (140,000 pairs), also masked boobies and three types of Darwin finch.

Espanola (aka Hood), southernmost of the islands, famous for seabirds—masked and blue-footed boobies and especially waved albatross, some 12,000 nesting pairs active in various stages January–April, almost the whole world population.

Fernandina, most westerly, with impressive lava flows, penguins (nesting in September–October), flightless cormorants, hordes of marine iguanas.

Isabela (aka Albemarle), largest of the islands (1,803 square miles, 4,670 km2), with volcanoes, especially Volcan Alcedo where hundreds of tortoises live amid steaming fumaroles (it’s a steep climb up and down to see them), also lagoons with flamingos and migrant birds.

Best times to visit generally are May–June and November–December.

Click on image for description

Antisana Ecological Reserve—463 square miles (1,200 km2) in Napo Province with prodigious wildlife, especially birds, not fully censused because of steep, difficult terrain in the Cordillerade Huacamayos, covered by lower montane and montane cloud forest with dense bamboo-dominated understory and almost constant rain or cloud cover. Inhabitants include black-and-chestnut and solitary eagles, lyre-tailed nightjars, orange-breasted falcons, greaters cythebills, flame-faced, paradise, and vermilion tanagers, greenish pufflegs, scarlet-breasted fruiteaters, and many, many more. At Lago Micacocha are silvery grebes, black-faced ibises, and carunculated caracaras. Mammals include spectacled bears, pumas, mountain tapirs, Culpeofoxes, and Brazilian rabbits. Lower elevations are more easily reachable from Tena, where accommodations are better; they’re simpler in Baeza, but roads are better. Either way, a good guide is important.

In early 1999 President Jamil Mahuad issued a decree blocking future oil exploration, mining, logging, and colonization in the Cuyabeno-Imuya and Yasuni National Parks which together protect some 4,219 square miles (10,930 km2) of old-growth rain forest. Part of the lush and biologically rich Amazon basin, they contain a vast river and lake system, thousands of plant and animal species—considered one of the most biologically diverse in the world—as well as indigenous peoples unchanged there for thousands of years. It is a great victory, though challenging to make it stick. Both areas have been (and still are) under threat from various causes, especially poaching of rare birds and animals, of which most of Ecuador’s most spectacular species are represented here.

Yasuni’s western border is 190 miles (306 km) from Quito, reachable only by motorized canoe. Several good lodges are on or near the park’s border, however, with trails, boardwalks, and guides; trips can be arranged in Quito.

Visit Tripadvisor®

for lodging information about this Reserve

Advertisement