Peru

“Dazzling scarlet macaws wheel and squabble with multihued parrots of 28 species, sometimes hundreds together, shouldering one other aside for places to snatch mineral-rich billsful of clay from cliffs along the meandering Madre de Dios River in Manu National Park.”

Peru ranks with Colombia in having as great diversity and concentration of wildlife—including spectacular birds—as any other country on earth, in almost innumerable habitat niches.

From Pacific coastal desert, one of the driest places in the world, to jagged heights of the Andes, dropping to deep, almost sea-level Amazon jungle swamps live powerful jaguars, rare spectacled bears, and shaggy maned wolves, among hundreds of other mammal species including tapirs, tree sloths, 32 species of monkeys, and 152 kinds of bats.

Velvet-coated cameloids—guanacos and vicuñas with perhaps the softest, most valued pelts of any animals—graze mountain meadows, and there are some 1,800 bird species, almost twice as many as in all of North America.

Giant Andean condors with silvery-white wingpatches soar over peaks on 10-foot-plus (3-m) wingspreads, fingerlike primary feathers spread to catch every thermal nuance. Brilliant scarlet macaws and rainbow-hued parrots crowd jungle stream banks, hundreds at a time, for valuable dietary minerals. Bejeweled hummingbirds of 100 species described by names such as sapphirespangled emerald, festive coquette, and black-eared fairies, sip nectar at all elevations. And there are remarkable Amazonian umbrella birds, orange-crimson Andean cocks-of-the-rock, marvelous spatule-tails, melodious nightingale wrens, great potoos, and long-whiskered owlets.

Tremendous biodiversity results from continuous overlap of almost innumerable microhabitats created by variable combinations of elevation, latitude, and moisture in Peru’s three main natural regions. In lowlands unaffected by ice ages, species have evolved without hindrance for eons. Over most of history the remote, forbidding character of Peru’s wild areas has discouraged exploitation (not all, as during the Spanish Conquest) and to a great extent it still does, though logging for valuable timber is a constant threat, as are mining, oil and gas exploration, cattle-raising, and other aspects of encroaching civilization.

Frisky dolphins, sea lions, and sea otters compete with huge swarms of seabirds—gulls, terns, pelicans, boobies, cormorants, and Humboldt penguins—for bounty from the Humboldt current running offshore most of Peru’s length. This strong current churns up cold water and nutrients from the deep Pacific. This creates coastal desert by holding moisture in the ocean— but its nutrients sustain a rich plankton community which supports vast fish numbers, prey base in turn for others.

Seabirds gather in the many thousands to feed over fish schools in a frenzied oceanic carpet of flapping, diving feathers. Islands such as the Ballestas off Paracas Peninsula support teeming colonies of water-oriented birds of dozens of species. One, the Guanay cormorant, is an economic treasure, its mountains of droppings harvested as guano, a potent natural fertilizer.

Life ashore is drier and sparser but notable. Plover-like Peruvian thick-knees wail plaintively. Small desert foxes sound like car tires screeching as they bark through the night (and sometimes day). Vermilion-headed Peruvian flycatchers flit over oases where rivers tumble from high mountains. Long-legged herons, egrets, and coral-pink flamingos forage in shallows, joined spring and fall by flocks of migrants.

Land rises precipitously from the desert, pushed up by tectonic plates to more than 18,000 feet (6,000 m) just 60 miles (100 km) inland. Pumas hunt in low riparian valleys but also venture up through stunted elfin woods and cloud forest homes of small, graceful Andean deer, velvet-furred chinchillas (Peruvian chipmunks), and shy little pampas and Andean cats, whose tracks have been seen at 16,000 feet (5,000 m). Diademed sandpiper-plovers pipe their calls. Patches of shrubby colorful polylepis cling to life at the highest elevation of any tree.

These eastern Andean slopes, among the least accessible and least known on the planet, are secure haunts of seldom-seen spectacled bears and mountain tapirs.

Other habitat variations occur as land descends again, more gradually, to the Amazon rain forest basin, which originates in Peru and makes up half the country—oldest continuous terrestrial habitat on earth. This is domain of giant river otters, bubble-gum-pink river dolphins, and slow-moving tree sloths.

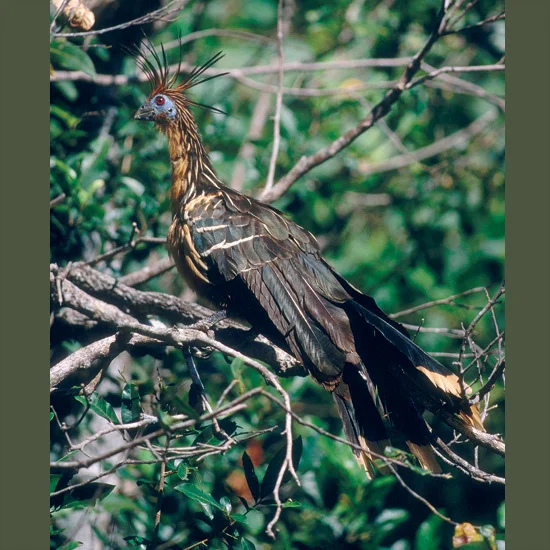

In this fragile but rich environment, over 6,000 plant species have been found in just one 250- acre (115-ha) plot. (Tropical rain forests cover less than four percent of earth’s surface but support over 50 percent of all its species, an estimated half of which have yet to be identified.) There are crocodilians in rivers, musky-smelling peccaries, bulky water-loving cabybaras—world’s largest rodents—and at least 1,000 bird species. These include prehistoric-looking hoatzins, whose young come equipped with claws enabling them to climb from watery riverside nests into overhanging trees where they clamber about until they learn to fly.

Over 12 percent of Peru’s 496,222 square miles (1,285,000 km2) is set aside in 56 protected areas within SINANPI—the Peruvian state protected area system.

They include:

MANU NATIONAL PARK AND BIOSPHERE RESERVE—a vast and stunning jungle of 6,600 square miles (17,100 km2), bigger than the state of Connecticut—with adjoining Alto Purus Reserved Zone, covers 10,000 square miles (25,900 km2), a huge protected area which scientists think may contain the richest flora and fauna of any place on the planet.

National Reserve of Pacaya-Samiria is Peru’s largest defined protected area, some 7,150 square miles (18,520 km2) of tropical forest at the heart of the upper Amazon in northern Peru, undeveloped at least until recently for tourism, but guides can be arranged in Iquitos or Lagunas.

Huascaran National Park, 1,170 square miles (3,030 km2), with high Andes species, a popular hiking/climbing area.

National Reserve of Pampa Galeras, 25 square miles (65 km2) near Nasca, set aside for rare vicuñas, smallest, most beautiful of South American cameloids brought near extinction for their precious soft fur.

Paracas National Reserve, an 1,295-square-mile (3,350-km2) coastal peninsula with stunning birdlife both onshore and just offshore at the Ballestas Islands, with huge nest colonies of penguins, pelicans, terns, boobies, cormorants, waved albatross, along with seals, sea lions.

These are immense, largely pristine areas designated by the National System for Conservation Units where nature is not controlled or organized. Many have minimal if any visitor facilities. In 1992 the Peruvian National Trust Fund was established, managed by the private sector, to provide funding to protect the country’s main reserves with help from the government and national and international nongovernmental groups such as World Wide Fund for Nature, The Nature Conservancy, the World Bank facility, and U.N. Environment Program.

There is also Colca Canyon, said to be the world’s deepest terrestrial chasm—twice as deep as the Grand Canyon—where it is sometimes possible at the rim to view soaring condors at eye level. Snows across the canyon at Mismi peak—elevation 18,200 feet (5,600 m)—are birthplace of the mighty Amazon River.

Best time here is the May–September dry season; otherwise travel can be difficult with roads sometimes impassable, flights cancelled, and landslides blocking train and bus routes (also, clouds can obscure spectacular scenic views).

Threats include mining, oil and gas exploration, grazing, poaching, and illegal logging, particularly of high value mahogany trees.

Peru

as well as...

Alto Purus Reserved Zone

National Reserve of Pacaya-Samiria

Huascaran National Park

National Reserve of Pampa Galeras

Paracas National Reserve

Colca Canyon

MANU NATIONAL PARK

More about the Reserves in Paraguay

Each button selection will take you to a site outside the Nature's Strongholds site, in a separate window so that you may easily return to the reserve page.

Advertisement