Svalbard

One-ton walruses laze in the sun, reindeer graze, and more than a million seabirds nest in summer on Svalbard, northernmost point of Europe’s northernmost country—nine small islands in the Arctic Ocean, just south of permanent pack ice.

Polar bears den here in large numbers. Arctic foxes with fur that offers better insulation from cold than any other animal—smoky-gray in summer, white in winter— follow them around, even out on drifting ice floes, hoping for seal meat scraps.

Diminutive little auks, which spend the rest of their lives entirely at sea, raise downy chicks on stony slopes and cliffs all over the archipelago, their nestlings’ shrieks audible as a steady summertime buzz all over the Longyear Valley.

Their breeding activities trigger an essential connection in the arctic land–sea ecosystem. When birds bring organic material from sea to cliffs to feed themselves and their young, food bits fall to terrain below along with feathers, carcasses of dead birds and fish, and their own droppings (guano), which fertilize growth of lush vegetation important for herbivores such as barnacle and pink-footed geese and reindeer. Meanwhile predators such as arctic foxes, glaucous gulls, and great and arctic skuas feed on both eggs and young birds to build up energy reserves for winter.

With the auks are thousands of individuals of other species—Brunnich’s guillemots, fulmars, kittiwakes, purple sandpipers, ivory gulls, red-throated loons (or divers), long-tailed ducks (or oldsquaws), red (also gray) phalaropes.

Arctic terns—world’s longest-distance migrants, wintering a hemisphere away—dive fiercely on interlopers near their nest scrapes. The only songbirds among 30 bird species are hardy little snow buntings in bright black-and-white breeding plumage, sweetly trilling after a 700-mile (1,126-km) flight across the Barents Sea, smallest bird to make that often stormy crossing.

Stout, short-legged Svalbard reindeer—smallest of the world’s reindeer, sometimes called Svalbard caribou—graze hungrily on moss and lichens, having dropped a third of their weight when winter darkness and cold made greenery scarce.

Like all the islands’ mammals, both land and marine (polar bears are classed as marine mammals), they were hunted to near-extinction in the last century, but after years of protection all (except for whales offshore) are once again common. Polar bears up to eight feet (2.5 m) long, weighing almost a ton, cover great distances with their fluid loping gait, and can be anywhere on the archipelago. They are so powerful, irascible, and unpredictably aggressive that all other creatures—including humans—keep a constant lookout for them.

Huge bull walruses with tusks up to two feet (0.6 m) long, temporary bachelors, await females’ return from summer sojourns farther north. They mate in midwinter—some think in the dark freezing water. Their enormous tusks seem, like deer antlers, to have social rather than practical function—food is located largely by touch, using highly sensitive nasal skin and whiskers to find crustaceans in pitch-black water, unearthing them on beaches in summer using tough upper nose skin or by shooting high-pressure jets of water from their mouths (an ability well-known among zookeepers).

By late summer all residents that can fly away are gone except for Svalbard ptarmigans which (like arctic foxes) molt from dark to pure white so that against snow only their dark eyes and bills are visible as they pick around scrubby growth for dwarf birch buds and willow catkins, even conifer needles if hungry enough.

Once Svalbard was lush tropical jungle, roamed by Iguanodon dinosaurs whose footprints are still visible in hardened sands near Barentsburg. Some of the oldest rocks on earth—fragments up to 3 billion years old—came to rest on this now-desert island group before it drifted north 60–300 million years ago carrying layers of organic material which became rich coal seams that now drive Svalbard’s economy.

Now 60 percent of Svalbard is covered with sheets and rivers of ice outlining mountains and glaciers in dramatic landscapes of breathtaking beauty. Over them upper atmosphere electrons create spectacular multicolored aurora borealis displays when they collide with charged sun particles in midwinter skies.

Air this cool with no moisture burden is so clear it changes distance and depth perception. Barry Lopez in his book Arctic Dreams reports a Swedish explorer had all but completed a written description of “a craggy headland with two unusually symmetrical valley glaciers, the whole of it part of a large island” when he discovered what he was looking at was a walrus.

Best times are spring and summer. Mean annual temperature is 25°F (–4°C), in July 43°F (6°C), though it can soar a dozen degrees over that, warmed by the Gulf Stream which reaches Svalbard’s western side. Midnight sun is from April 20–August 20, deep polar night October 28–February 14, the rest something in between. Svalbard’s small population marks the sun’s return on March 8 with annual parades and celebration.

Serious threat to the wildlife reserves that cover more than half of Svalbard (and 72 percent of waters around it) is human-produced pollutants transported, it’s believed, from distant sources by wind and ocean currents. Scientists have found PCB levels in polar bears so high they fear it could lead to reduced reproduction and higher mortality.

Svalbard is reachable by scheduled air daily in clear weather—and by ship in summer—from Tromsø to Longyearbyen, which has lodging, restaurants, and tour facilities. A ferry with cabins makes weekly summertime cruises around northern Spitsbergen. Tromso has direct air connection with international jetports at Oslo and Bergen.

Visiting Svalbard is not always easy. Local transport can be a problem, permission is required to visit parks, sensitive nesting areas are off-limits, and independent tourism not encouraged. Dangers are such from polar bears, drift ice, weather, and terrain, that rescue insurance can be required for visits to remote areas. Bears cannot legally be shot except in extreme danger and only if all other means of self-defense have been exhausted.

Most visitors opt for group tours, which are organized in Spitsbergen and Longyearbyen.

Highlights of Svalbard’s wildlife reserves include:

Forlandet National Park—King and common eider nesting, world’s northernmost harbor seals.

The Island of Hopen in the Barents Sea. Hopen is protected as a nature reserve, and is a denning area for polar bears. Hopen is also listed among Birdlife International’s important bird areas in Europe, due to the large colonies of seabirds such as Brunnich’s guillemots and kittiwakes.The waters surrounding Hopen are also a winter habitat for walruses, and there is a haul-out site on the southern part of the island.

Moffen Nature Reserve is a walrus haul-out area, also nesting birds.

Nordenskold Land National Park, south of Longyearbyen, which includes some of Svalbard’s richest areas of lowland tundra, including wetlands in Reindalen. The park is an important area for Svalbard reindeer. The western part of the park includes seabird colonies and habitats for species such as eiders and barnacle geese.

Nordre Isfjorden National Park includes areas of rich tundra vegetation on the coastal plains north of Isfjorden and includes wetlands and complexes of small lakes and ponds that are habitats for waders and waterbirds such as eiders, barnacle and pink-footed geese. The fjords here are also habitats for ringed seals.

Northeast Svalbard Reserve has bear denning, strictly protected from all traffic including aerial overviews.

Northwest Spitsbergen National Park with large seabird colonies, reindeer, fox, walrus haul outs, historic sites including remnants of failed schemes to reach the North Pole in hydrogen-gas balloons.

Sassen-Bunsow-land National Park in the inner part of Isfjorden includes areas of lowland tundra which are also habitats for reindeer. It also includes areas for waders and waterbirds, including a Ramsar site at the islets of Gasøyane (nesting site for barnacle geese). The fjords harbor ringed seals.

Southeast Svalbard Reserve has a large reindeer population, and many polar bears.

South-Spitsbergen National Park has nesting eiders, barnacle geese, large seabird colonies. There are also 15 special bird reserves for nesting eiders, and barnacle geese and others, mostly on small islands along Spitsbergen’s west coast, strictly protected, plus two plant protection areas.

Svalbard is among hundreds of Norwegian nature set-asides.

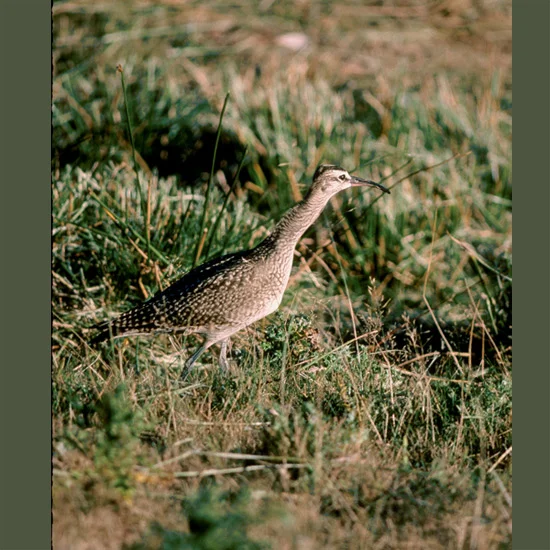

Click on image for description.

Visit Tripadvisor®

for lodging information about this Reserve

SVALBARD as well as...

Forlandet National Park

Island of Hopen Nature Reserve

Moffen Nature Reserve

Nordenskold Land National Park

Nordre Isfjorden National Park

Northeast Svalbard Reserve

Northwest Spitsbergen National Park

Sassen-Bunsow-land National Park

Southeast Svalbard Reserve

South-Spitsbergen National Park

Advertisement